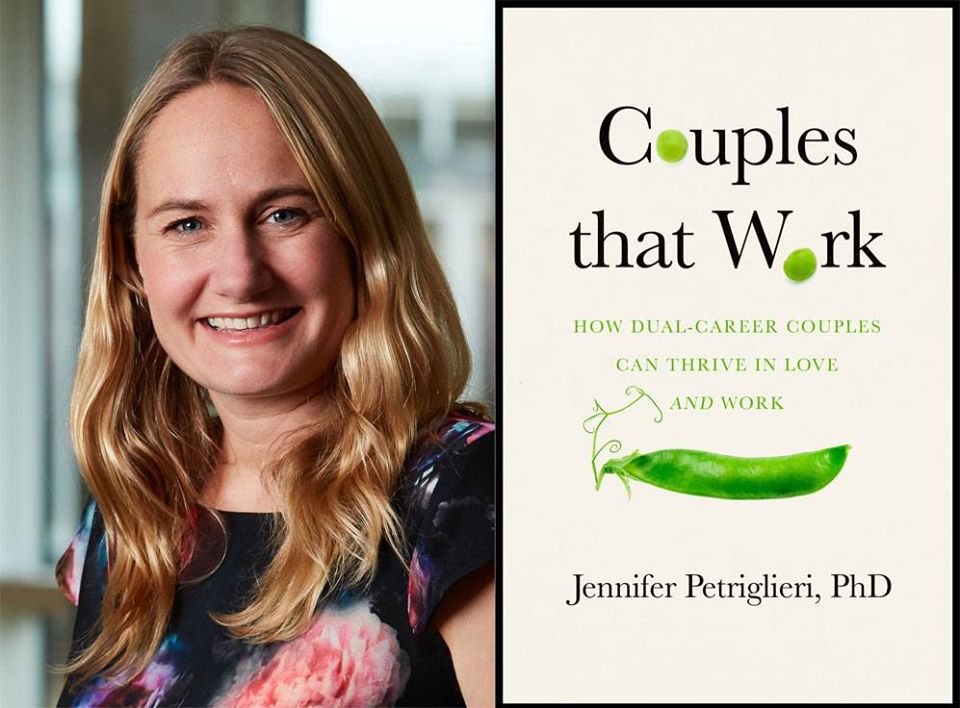

Jennifer Petriglieri is a British academic and researcher, and the author of ‘Couples that Work: How to Thrive in Love and at Work’. She is also a Professor of Organisational Behaviour at INSEAD in Paris. HR Magazine spoke to her about the upcoming book, discussing issues related to HR and talent in the workplace.

A unique viewpoint

The marketplace for business and working-life literature is already heavily saturated, but Petriglieri explained her reason for jumping into this crowded pool. She said, “There’s nothing else like this out there. None of the available literature deals with the issue of couples in the right way. For the last 15 years, I’ve been researching careers, career transitions and leadership development and I was increasingly hearing from people that if you want to understand their career journey you need to understand their partners.”

As an academic and a writer, Petriglieri looked around and saw that there is a lot available to read on work-life balance and sharing the roles at home, dividing child care, and so on. But, there is nothing that really speaks to the intersection of careers. Often, in books and media, careers are talked about as if there are no-strings-attached. A career is often looked at as a separate entity to the interaction between couples who both have a working life.

Setting boundaries

The key to being a successful dual-career couple, according to Petriglieri, is decision making. She elaborated, “The core thing is that it doesn’t matter what you choose, it’s about how you go about choosing it. For example, having kids, moving homes, any decision—the couples who do well are the couples who take time to really think through their choices together at a fundamental level.”

This means it is not just about decisions on the usual issues, such as money or childcare. The key is to take time to create the foundation—what matters to us as couples? Where do our ambitions lie? What can often happen is that a decision is made, quickly, based on money (or ease) and eventually, you wake up one morning wondering ‘whose life am I living?’ Whereas, successful couples are those who spend time on the basic layers of their relationship, especially setting the boundaries—and make their decisions on that base level to align with both parties.

Hedging bets

Dealing with challenges becomes easier if you have these boundaries in place. For example, when companies offer a promotion opportunity or management training plan, if it falls outside of the couple’s prescribed boundaries, then the opportunity will be passed up. The relationship’s core goals overtake individual career choices.

Younger generations, increasingly on two-incomes, tend to be better placed to deal with such problems and these couples have a greater tolerance toward them. They can hedge their bets more, as there is a fallback. Due to some companies still being stuck in the ‘old ways’ and not thinking of the employee’s partner’s life, they risk losing out on talent. Petriglieri added, “There are fewer ‘tagalong’ partners, who might be able to move around with the other more easily. So, an example such as an employee who is offered the chance to move to different countries may be less willing to accept the opportunity as it does not fit within the boundaries of the relationship. Demographers argue that couples have more power now, due to a double-income, meaning they can walk away from a company if the opportunities do not fit their life choices.” This power-dynamic was not so common in the past.

The future of work

Going forward, companies need a new strategy if they are to retain the best talent. In one of Petriglieri’s surveys, she asked a company’s VP of HR, ‘Why does your leadership ladder look like that?’ The organisation replied that they need experience in certain markets, but when asked ‘why?’, they were not clear, answering ‘because that is what the guys at the top did’; the implication being that they were perpetuating outdated models of hierarchy.

Those companies on the cutting edge are moving away from that and looking at the skills needed instead. Old methods are no longer as efficient at talent management. The newer, fresher leaders, according to Petriglieri, “Are using a more bespoke approach that fits the employee and their life, rather than just thinking of the employee as a single entity.”

Egalitarianism

A rise in egalitarianism is seeing women more able to express their need for a meaningful career, as well as men who feel free to express their desire to be more hands-on at home. This equity means both partners have a stake in decision making, which affects their working life and, by proxy, the companies they work for who, if they want to retain such talent, need new methods of accepting these cultural changes. Petriglieri added, “Research appears to show that men who have working wives, or daughters who work, are more egalitarian as managers. They have empathy and understanding. The mechanism of their managerial improvement is their experience and understanding. They ‘get it’.”

Petriglieri is not confident that enough companies ‘get it’ at the moment. There appears to be a lot of work still to do for HR leaders if they are to fully embrace the modern dual-career couple in an effective way. Those couples who are successful in their relationship will not be as persuadable as the talent from previous generations; therefore, if organisations want to recruit the best talent, they need to be more adaptable, flexible and better understand the trends.

A review of ‘Couples that Work’ can be found in the book review section of this issue.